While other small car manufacturers scream to get their clients’ attention with over-the-top styling and useless power, subtle understatement is the name of the game for Turin-based restomod operators Officine Fioravanti. Their latest gem: a manual Alfa 8C.

It’s a quiet Sunday morning in Morbio Superiore, a small village in Ticino, Switzerland. Tusco Cavalli, the founder and owner of Officine Fioravanti – the company that became an overnight internet sensation a few years ago with their Ferrari Testarossa restomod – is showing us around his father’s house. Designed by Peppo Brivio and built between 1962-63, Casa Corinna is one of Switzerland’s earliest brutalist private residences and one of the first houses in the country with a flat roof. A triumph of design composed of interlocked cubes, in which warm brick and wooden surfaces touch cold concrete and steel. It’s a minimalist, airy structure full of light and thoughtful details. The house features gigantic windows overlooking the valley below, an inner courtyard offering peace and shade, and – most importantly – a two-car carport in which the two machines we will be taking out today are parked .

While making coffee, Tusco is pointing out to various design and art pieces that fill the structure, his father being an avid collector. He expertly explains ideas behind the intentions of designers and artists, while Giorgio Richetti, his right hand man whom he has known since high school, is directing the flow of movers and cleaners who are removing all evidence of the decadent party that was apparently held at the house last night.

“We had fire-breathing women acrobats dressed in feathers, you know” Tusco says with a charming grin. We grab the coffees and he shows me around the grounds. Surprised, I point to a large, 3×3 meter hole in the lawn. “Normally there’s a hot tub in there,” our host explains. “But when we throw a party, a helicopter comes and takes it away, so that we can use the pit for a bar.” For a man who has partied until break-of-dawn he looks as fresh as a daisy. Or maybe it’s because he is only 25 years old.

All this, as well as the fact that this extraordinary young man started racing Ferraris in the GT3 class when he was only 15 together with our friends from Kessel Racing, is important to this narrative. The Ferrari 512 BB in the driveway belonged to the family since new – and it is the car in which Tusco learned how to drive a manual. Did everyone in high school and at university hate him? “Most definitely.” he says. “Partly because I was the only kid with a parking spot beneath the school” – a catholic establishment both Tusco and Giorgio attended – “But mostly because I was partying with the professors instead of my peers.”

The history of cars and brands is the history of people behind them. So, understanding where they come from and who they are makes the job of decoding the vision behind their products so much easier. In this case the theory is as accurate as it gets. Tusco is an eccentric, well-educated, 25 year-old race car driver who is passionate about art and engineering. He’s slightly decadent, with perfect taste. Seemingly born with a silver spoon in his mouth, but also somehow down to earth, pragmatic, approachable and friendly. Translate those traits to cars and you get Officine Fioravanti’s Alfa Romeo 8C conversion and Ferrari 512 BB upgrade I am about to experience.

“I bought the 8C because I love the looks and the sound that it makes, but I never cared for the way it drove,” Tusco says. “The problem is the standard robotised manual gearbox, which is slow, jerky and which limits the engine’s potential to protect the clutch” he adds. “I was coming back home from the racetrack once, driving over some mountain roads and at one point an Audi RS3 overtook me. I won’t have that, I said to myself while grabbing one of the paddles to downshift. I pressed hard in order to follow him, but he simply disappeared in the space of the next three or four corners,” he explains. “It was then that I made the decision to upgrade my 8C so that it reaches its full potential.”

He ‘cued the music’ and got to work. The gearbox was replaced with a beautiful open-gated manual, with a custom-made housing, an open pore wooden knob with an 18-karat gold coin embossed with the Officine Fioravanti logo. The car underwent a diet, shedding some unnecessary kilos in the process. Integrated vehicle management electronics with new systems were added, unleashing more power from the engine. Electronically controlled, adjustable Öhlins suspension with military-grade connectors and a carbon-ceramic braking system followed. Inside, the old seats were scrapped in favour of OF-designed carbon fibre monocoque seats with FIA approval, developed in collaboration with Laboratori Meccanica Torino, known as LMT. This not only improved the comfort and driving position, it also made it possible to drive the car on track with the removable magnetic head cushion option while comfortably wearing a helmet. All this without forgetting about aesthetics – the leather bits were reupholstered in ostrich leather.

Experienced in person, the true impact of these subtle changes are visible only upon closer inspection. The car sits on Pirelli P Zero Trofeo RS tyres wrapped around bespoke Officine Fioravanti forged five-spoke wheels. There is a little red “m” badge on the boot lid. The clutch and brake pedals are smaller replicas of the pedal on the standard 8C, with the subtle addition of the OF logo to the clutch. The elevated, gated manual, with exposed linkages, has a beautiful little pawl that prevents an accidental shift to reverse.

On the road, and in Tusco’s hands, the 8C turns into an absolute beast with the immediate throttle responses of a thoroughbred racing car, plenty of power and torque, and fantastic roadholding thanks to improved chassis dynamics and those fat semi-slick tires. The price of the conversion is unknown, but to be honest: if I were an Alfa 8C owner, I would give Tusco a call today, as this disappointing slowcoach of a car finally can put its money where its mouth is, pulling serious Gs in corners and putting a massive smile on any driver’s face.

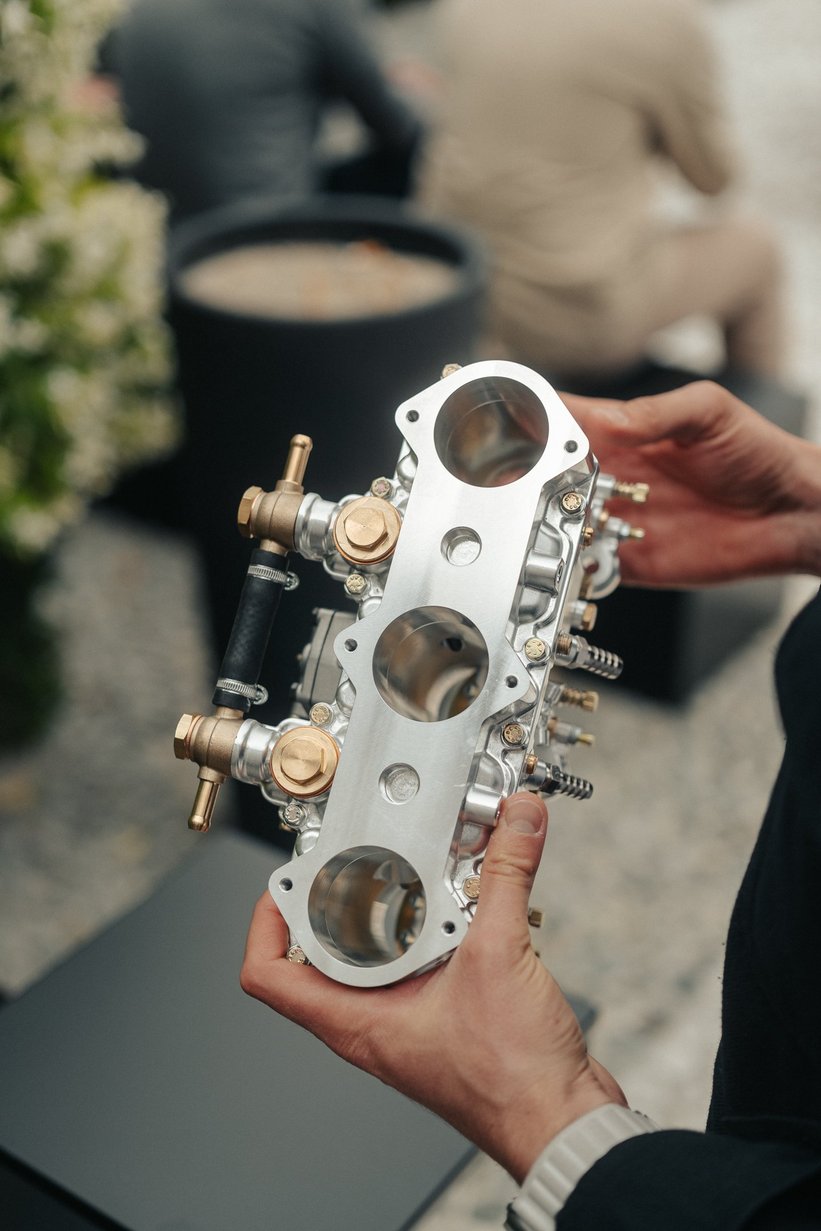

We subsequently move to the family heirloom that is the fantastically patinated Ferrari 512BB. To see what has been done to this car is almost impossible, but the results are even more profound than on the 8C, albeit completely and easily reversible. Instead of the standard carburettors, which restricted the performance of the flat-12 engine, a clever fuel injection system was designed, engineered and fitted. Machined from a single block of solid aluminium, it is disguised as a carburettor, but allows (thanks to a modern electrical system and a hidden computer brain) for a more precise and unobstructed fuel-air mixture, which in turn makes the car more reliable and better to drive.

It starts instantaneously, doesn’t smell (which makes it more usable as a daily, as you don’t arrive to your meeting smelling like a petrol station employee), and also – which is probably the biggest party trick – is incredibly torquey. We easily make our way up the hill in 3rd and 4th from as low as 1000 RPM. We also perform perfectly smooth standing starts in second gear without burning the clutch by adding excess throttle. When we do push it, the power is even more visceral than on an original 512. Sure, it doesn’t pop and bang on the overrun, but getting from sea level to the top of an alpine pass doesn’t require tuning the carbs by a skilled mechanic.

“I’m sure purists will hate us, but I think that for my generation, upgrades like these are necessary to keep these cars on the road,” Tusco says while cutting through several subsequent corners with his foot firmly planted into the floor. It’s hard not to agree with him. We arrive on the shores of lake Lugano for an early lunch.

What is the price of these conversions? I ask him finally. “For now we haven’t set a definitive price list, as we are focusing on moving to our new facilities in Torino” he says. “But let’s say that the extensive testing I have done in the area has cost me dearly. I got caught by a speed trap and might have to do a little bit of jail time. Annoying as I am about to have a kid,” he adds with a Robin Hood Prince of Thieves style grin. This guy! I mean… this guy!

Photos: Błażej Żuławski for Classic Driver