Scientists have estimated the Earth to be more or less 4.54 billion years old, predating even human existence. Indeed, there’s a lot more to learn about our home planet than what we were taught in schools. So, when a photo of an unusually massive bird claw surfaced online, people couldn’t help but be astounded by it.

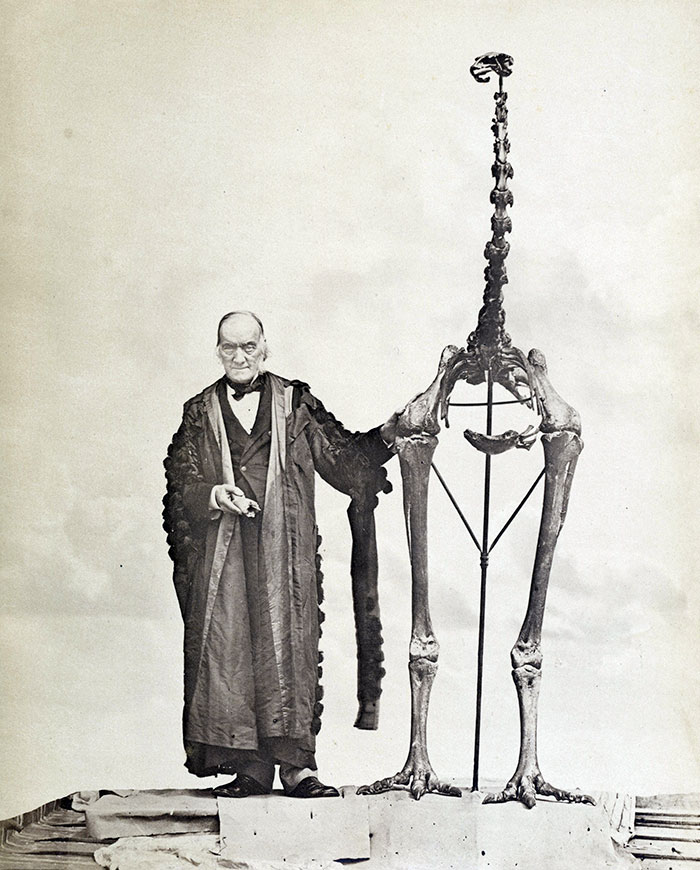

The giant claw was discovered by the members of the New Zealand Speleological Society in 1987.

They were traversing the cave systems of Mount Owen in New Zealand when they unearthed a breathtaking find. It was a claw that seemed to have belonged to a dinosaur. And much to their surprise, it still had muscles and skin tissues attached to it.

Later, they found out that the mysterious talon had belonged to an extinct flightless bird species called moa. Native to New Zealand, moas, unfortunately, had become extinct approximately 700 to 800 years ago.

So, archaeologists have then posited that the mummified moa claw must have been over 3,300 years old upon discovery!

The claw turned out to have belonged to a now-extinct flightless species called moa.

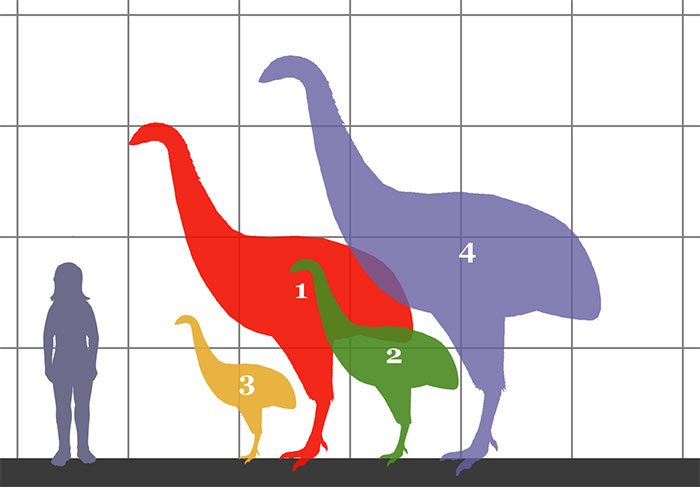

Moas’ lineage most likely began around 80 million years ago on the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. Derived from the Polynesian word for fowl, moas consisted of three families, six genera and nine species.

These species varied in sizes—some were around the size of a turkey, while others were larger than an ostrich. Of the nine species, the two largest had a height of about 12 feet and a weight of about 510 pounds.

Moas varied in sizes—with some as small as a turkey and others as big as an ostrich.

The now-extinct birds’ remains have revealed that they were mainly grazers and browsers, eating mostly fruits, grass, leaves and seeds.

Genetic studies have shown that their closest relatives were the flighted South American tinamous, a sister group to ratites. However, unlike all other ratites, the nine species of moa were the only flightless birds without vestigial wings.

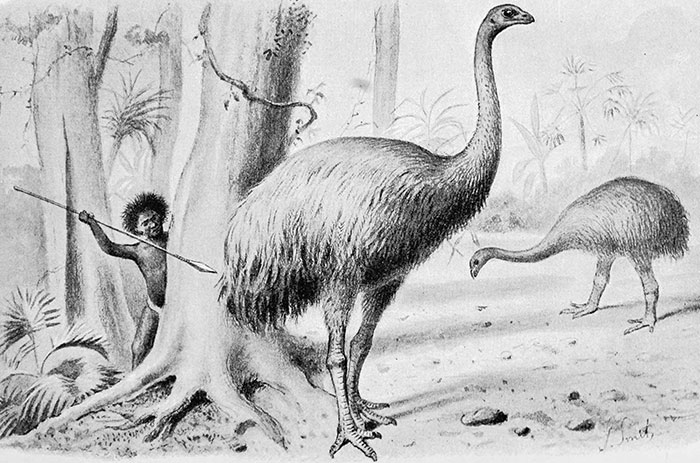

Moas used to be the largest terrestrial animals and herbivores that dominated the forests of New Zealand. Prior to human arrival, their only predator was the Haast’s eagle. Meanwhile, the arrival of the Polynesians, particularly the Maori, dated back to the early 1300s. Shortly after, moas became extinct and so did the Haast’s eagle.

Sadly, they became extinct shortly after humans arrived on the island

Many scientists claimed that their extinction was mainly due to hunting and habitat reduction. Apparently, Trevor Worthy, a paleozoologist known for his extensive research on moa agreed with this presumption.

“The inescapable conclusion is these birds were not senescent, not in the old age of their lineage and about to exit from the world. Rather they were robust, healthy populations when humans encountered and terminated them.”

But whatever brought about these species’ extinction, may their remains serve as a reminder for us to protect other remaining endangered species